Depth of knowledge

Author: Stacey Maifeld

Author: Stacey Maifeld

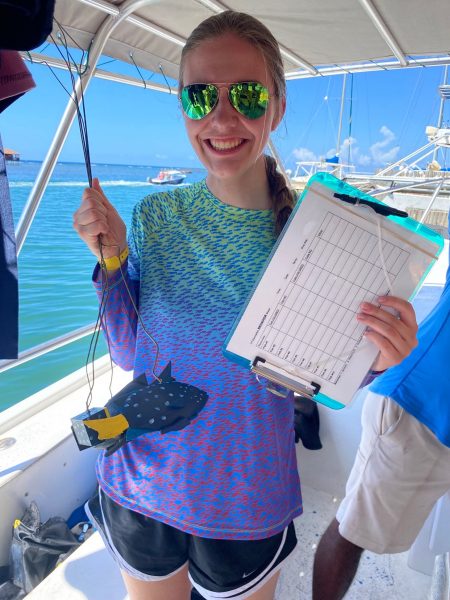

With data collection sheets in hand, Jamie Hefley (’23 biological pre-medical illustration) scuba dove into blue-green Caribbean waters off the island of Roatán. She hoped to survey a species in the wild that she had studied online back at Iowa State — Spirobranchus giganteus, or as it’s commonly named, the Christmas tree worm.

Hefley and her research partner were in luck. They didn’t observe just one of the colorful annelids. During their eight-day biology field course, they surveyed over 157.

“I was so excited!” Hefley said. “I thought, ‘They’re here, they exist!’”

Hefley was part of a small group of Iowa State students who traveled over spring break to Roatán for Iowa State’s Biology 394 class, a Caribbean marine biology field course.

Roatán is located off the coast of Honduras on the Mesoamerican Barrier Reef, the world’s second largest barrier reef system. A dive destination, it’s also home to the Roatán Institute for Marine Sciences, a research and teaching institution.

Don Sakaguchi, Morrill Professor and director of Iowa State’s undergraduate biology and genetics programs, co-led the spring semester course with Jeanne Serb, associate professor in the Department of Ecology, Evolution and Organismal Biology. This was Sakaguchi’s 11th time leading the unique, hands-on learning experience.

“We continue to do this because it’s a great opportunity for our students and because the students have been great ambassadors of Iowa State,” Sakaguchi said. “The people at the institute really like Iowa State because they like our students. As soon as we arrive at the airport, we are greeted with open arms. It really is like going to see friends when we are down there.”

In 1998, Sakaguchi was approached by Warren Dolphin, Iowa State emeritus professor of biology and former biology program director, about helping lead a new international marine biology field course. It proved to be a perfect fit. While Sakaguchi’s research is in neuroscience and stem cells, he has a personal passion for diving. As a former advanced open water scuba instructor, he experienced some of the best diving in the world, from the island nation of Palau in the Indo-Pacific region to the Great Barrier Reef along the coast of Australia.

“I had an opportunity to dive all around the world and develop a strong interest in preservation of marine environments,” Sakaguchi said. “This was a great opportunity to develop this course, share my experience with students and expose them to a different ecosystem in a different country. Our goal is that students gain a tremendous appreciation for the extreme diversity in the oceans and the importance of the coral reefs.”

Biology 394 is a semester-long course. Prior to spring break, students attend a weekly seminar on campus where they prepare for international travel and discuss topics such as coral reef ecology, marine invertebrates and fish. Each student is required to be comfortable with snorkeling or scuba diving, and some students prepare for the trip by earning their first scuba certification and open water certification.

They also develop research projects to conduct on the coral reefs off Roatán, such as Hefley’s analysis of the relationship between the Christmas tree tube worm and its host corals.

“They’re really cute and vibrant,” said Hefley, a talented scientific illustrator. “Because annelids in the sea aren’t commonly recognized in research, my research partner and I wanted to do something on that.”

Hefley and her partner Ally Abel (’23 biological pre-medical illustration) searched for Spirobranchus at four different reef locations, surveying its presence on 73 individual coral colonies.

“We looked for several indicators of coral damage: scarring, algal growth, and discoloration,” Hefley said. “Due to lack of tissue, damage could not be observed on dead coral, however, we did observe the presence of damage in the majority of live coral on the tissues surrounding the Christmas tree tube worm. We believe this suggests a negative relationship between Spirobranchus and their host coral.”

Abigail Krull (’24 genetics) and her research partner Sydney Honold (’23 genetics) chose to do a behavioral study on yellowtail damselfish and dusky damselfish. In preparation, they used a 3-D printer in the basement of Lagomarcino Hall to print four variations of fish- and block-shaped stimuli.

“Fish are traditionally territorial when they are threatened, especially around their little algae farms, so we wanted to see if that territoriality was triggered by the shape of a stimulus or the color,” Krull said.

Though they never observed a full-on attack during their research at Roatán, they witnessed lots of interaction, Krull said, which was a thrilling learning experience.

“We had studied the species through a book or a screen, so it was super cool to see them out in the wild,” Krull said. “I was like, ‘This can’t be real! I saw it on a screen a couple of weeks ago!’ The whole experience felt surreal — I had to force myself to be in the moment.”

Each day at Roatán, the class completed multiple dives and snorkels and attended morning and evening lectures on fish identification, coral identification, reef survey methods, native turtle species, coral restoration and more.

In addition to their lectures and research, the class explored the arts and culture of Honduras at the Mayan Interpretation Center and the Ethnic Honduran Art Exhibit Center, and they also spent a day training with dolphins.

“If you go on this trip, you might get kissed by a dolphin,” Hefley said.

Perhaps the biggest highlight was Iowa State’s participation in the institute’s coral restoration project. Using fragmented elk horn corals that were harvested from the reef, Iowa State students dove down in teams to hang the fragments on nursery trees. The coral fragments then propagate and filter feed, and once they are bigger, they can be relocated and planted back into the reef.

“[Coral restoration] was one of the most rewarding things that I experienced there,” Krull said. “It was cool to see what the restoration work was like down there. It made me feel good that we’re doing something.”

Over the years, Sakaguchi has seen the quality of the reef decline, with multiple coral bleaching events and hurricanes, he said.

“It’s never recovered to what it was like back when I first dove there in 1998,” he said. “That’s what’s going on globally in terms of deterioration of the coral reefs. Right now, most recently there’s been a disease that’s ravaged a lot of the corals along the Atlantic and Caribbean called stony coral tissue loss disease.”

Some alumni of the course have pursued marine-related careers, such as working at aquariums or turtle reproduction centers, Sakaguchi said. But regardless of their future goals, the exceptional experience equips students with skills that will be useful in any field.

Krull aims to attend medical school and said the trip provided experiences she could not have received in a traditional lecture course, such as learning to adapt quickly in new environments.

“What I found so cool is the amount of information I learned from doing things while I was down there,” she said. “I have a new, reignited love for ocean restoration and marine biology in general and field work.”

Hefley said she is now interested in living near the coast someday and illustrating marine-related subject matter to further public knowledge about the oceans.

“I want to inspire and educate with what I create and show science through a beautiful lens,” Hefley said. “Most people don’t see it that way, but science is beautiful. I want the public to see it in that light.”

After diving together for hours, trading tips for graduate school over fish tacos, and basking in the camaraderie of a sun-soaked adventure, Krull and Hefley both said the friendships and connections they made with their peers and professors are lifelong.

“The best part was the relationships you come out of the trip with – you’re with these wonderful people for every hour of the day,” Hefley said. “We’ll never forget.”